The financial reality of living with a chronic illness

A transparent look at the numbers behind medication, part-time work, and more

Since I shared my last letter, many people have reached out to me about my issues with having access to my meds. I’ve explained the domino effect of high copays, tapped financial assistance resources, the nuances of marketplace health insurance, and the unreliable/insufficient income I make as a freelance writer to so many friends and family members that I realized this information needs to go into a post of its own.

Doctors have point blank told me that Rheumatoid Arthritis is an “expensive disease to have,” which is frankly mind-boggling that anyone would say this to a patient.1

I’m here to tell you today that chronic illness doesn’t only affect energy levels, mobility, the immune system, health in general—it affects one’s ability to live abundantly in multiple ways.

Chronic illness is not only expensive to treat and manage, it also affects one’s ability to earn. Let me break it down as simply and transparently as possible.

For starters, let me share what kinds of illness-related expenses I pay for on a regular basis:

Health insurance premium - $400 per month2

Specialty doctor (rheumatologist & dermatologist, for various symptoms) copays - $100 per visit

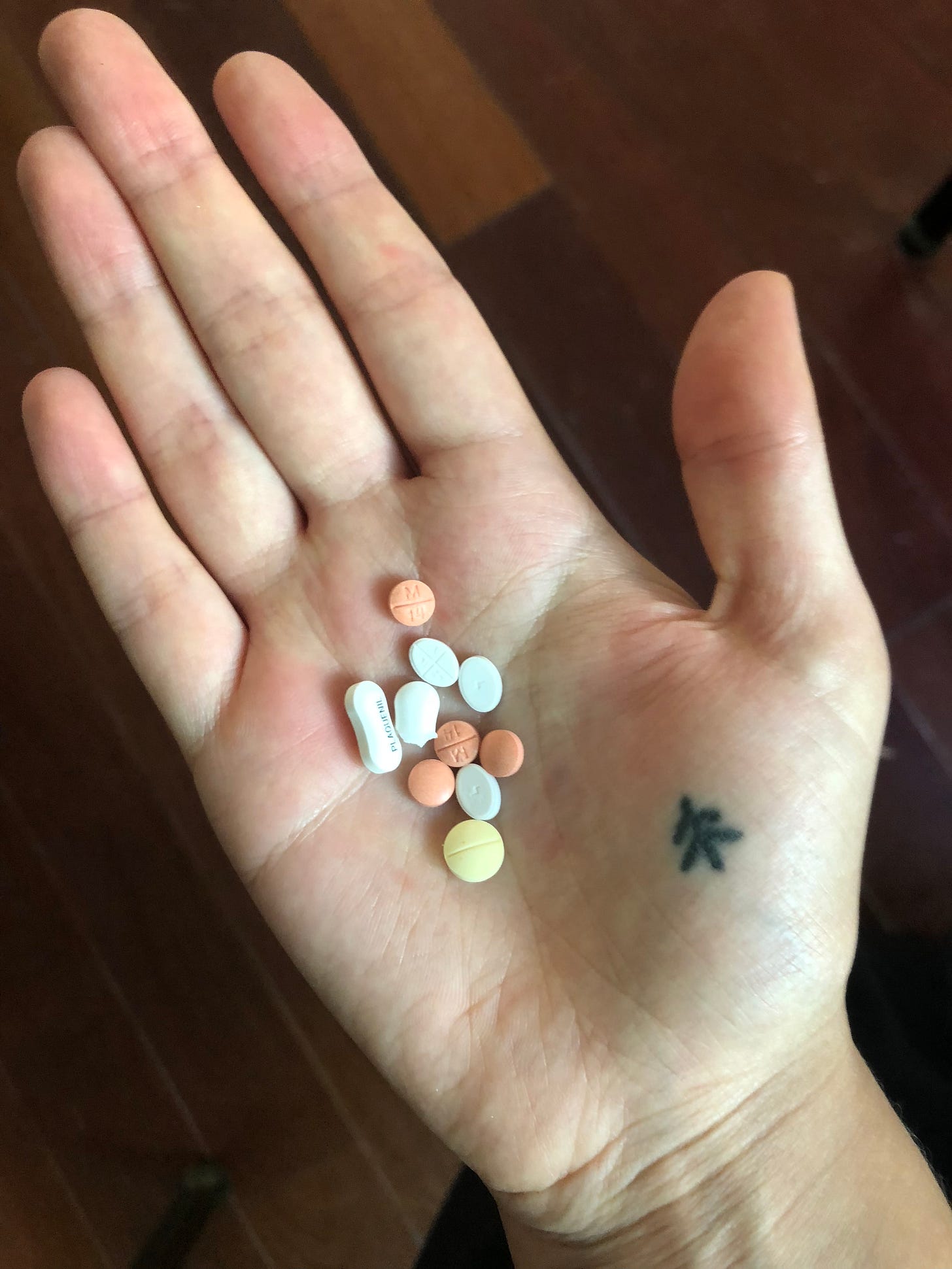

Medication copays - $36 for a 3-month supply of Sulfasalazine; $500 for a month’s supply of Orencia3

Rent (in a city that I consider a “healing environment”) - $2200 per month4

Groceries (for nourishing foods that help fight inflammation) - $800 per month5

Supplements (to further fight inflammation) - $30-150 per supplement, as needed

Personal care items (without toxic ingredients to keep toxicity levels low) - $30-150 per product6

Total illness-related monthly expenses: ~$4000 per month, give or take depending on supply levels

I thought about sharing with you all what my monthly income is, but including that number would be missing the point. The purpose of this letter isn’t to tell you all that I can’t afford to be chronically ill (spoiler: I can’t), the purpose of this letter is to show you that in order to manage a chronic illness effectively, you need a lot of resources. Resources that are, inevitably, more difficult to come by as a chronically ill person.

To be fair, I’m one of the lucky ones.

I make enough money from freelancing that I can get by without government assistance. There are millions of people who make far less—their health insurance is (for now) subsidized by the government. And, if you fill out mountains of paperwork, persevere when you’re rejected once or twice or even three times, and sit before a judge to make your case, you have a chance at receiving SSI and SSDI. But if you do, you’ll have your assets monitored and, essentially, strangled.

Here is what the creepy Google AI overview says when you search about these benefits:

Yes, marriage can affect Supplemental Security Income (SSI) benefits, and in some cases, it can make it impossible to receive SSI:

Asset limits: SSI recipients can't have more than $2,000 in assets, and couples can't have more than $3,000. These limits haven't been updated for inflation since 1984.

Income limits: If a recipient marries someone who isn't receiving SSI, Social Security considers their partner's income as part of their own. In 2024, if a recipient's spouse earns more than $472 per month, their income will be partially available to the recipient. If the couple's combined income is more than $1,415 per month, the recipient will no longer be eligible for SSI.

Living arrangements: Sharing expenses with a spouse can reduce SSI payments.

I don’t know about you, but reading this makes me so emotional.

Next, let me break down how living with chronic illness has made it difficult to earn:

So this point, like everything else in this letter, is purely subjective and situational, but the reality for 95% of my chronically-ill friends is that none of us can handle a full-time job because of how mentally, physically and emotionally taxing it is to work a 40+ hour workweek. That being said, it isn’t impossible. I know a couple of chronically-ill people who have full time jobs (and I’m certain there are hundreds of thousands who do), but I’m also pretty positive that each and every one of them would rather be working less if they could.

Part time work generally means you don’t receive health insurance benefits. I know this isn’t the case everywhere, and benefit requirements differ from company to company, so I’ll stop trying to cover every base and just focus on my own experience:

I work as a freelance copywriter (and sometimes book designer!) for a handful of clients. The money I make is not taxed, which means I have to put aside roughly 25% of that income to pay the IRS (in theory. I actually can’t afford to save for taxes at the moment… oops.) I also don’t receive any benefits from my clients like health insurance or paid time off. This means that if I’m not feeling well and have to take an afternoon or a day or a few days off, it directly affects my monthly income. This also means I’m paying out of pocket for insurance ($400/month, remember?)

I choose to work as a freelancer (right now) because I can also (somewhat) choose how many hours I take on in a week or a month. Currently, I work between 15 and 20 hours a week. There have been times in my life when I worked full time—8 hours a day, 5 days a week—and each time I took that much work on, I had to cut back.7 But… if you are an employer who happens to be reading this, know that I will never take on work that I can’t accomplish! I am very proud of my ability to meet a deadline. If I can work part time as a freelancer while earning my MFA (and writing the draft of a novel), I can probably handle a full time copywriting job ;)

That being said, right now I am freelance, so all of the benefits/self-employment tax stuff still stands, as it does for many of my chronically-ill friends who are in a similar boat.

Finally, let me say this loud and clear: capitalism is inherently ableist.

You heard me!!! And you probably know this already! Chronically ill people are at a major disadvantage in a number of ways. First, the financial burden of our illnesses that I mentioned before. Second, getting hired for any job so that you can pay for all of the expenses necessary for managing your illness requires—in this late-capitalist society, especially for Millennials and Gen Z people who inherited this bonkers economy—more than just experience and competence (both harder to come by when you’re chronically ill). Making money requires a certain zest. A go-getter’s attitude. A knack for hustling. A palpable hunger. An “I operate at 110% at all times” ness. You need to stand out, go above and beyond, to find “success” AKA money AKA security.

We, the chronically ill, simply don’t have enough energy for zest. Okay, okay, I’m selling myself and others short—I do think I possess a lot of zest, but only because I’m not that sick (I’m sick enough that I couldn’t walk last week, lol). Or rather, I’ve monetized my skills, and I’m incredibly lucky that my skills are in demand. But what about the chronically-ill woodworker with raging MS who can’t keep a board steady when they’re flaring? What about the ballet dancer with RA who has to drop out of the upcoming performance because they can no longer put weight on their feet? What about the farmer with Crohn’s disease who is doubled over with pain and can’t walk in a straight line, let alone harvest all of those carrots? You see what I’m saying? I’m one of the lucky ones!

I could go on about the other ways capitalism is ableist, but I won’t in this letter. That topic should—and will—have its own letter, I promise.

Okay, so what can you do?

If you’re chronically ill and are in need of financial support, I recommend:

Taking advantage of mutual aid to at least give you a security net. Izzy and I both launched GoFundMe campaigns in the past year, which helped enormously, though I don’t necessarily recommend using GoFundMe at this point.

See if you qualify for government assistance, such as Medicare, SSI and SSDI (but be aware of the limitations of accepting these benefits).

If you can monetize a skill that doesn’t require too much energy on your part, milk it as much as possible. (I’m lucky that my brain functions decently well as a freelance copywriter. If you have writing skills, artistic skills, math skills, tutoring skills, data entry skills… see if you can find a remote job in your corresponding field.)

This letter has really taken it out of me so I am honestly drawing a blank on anything else, but I hope people share ideas in the comments section!

If you’re not chronically ill and are financially stable, here’s how you can support your chronically ill friends:

Buy them dinner the next time you hang out

Literally just Venmo them randomly, lol (shoutout to

for gifting me the money to pay for my meds this past June! That was one of the kindest things anyone has ever done for me)Support whatever monetized skill they’re offering—hire them for freelance work if it makes sense; upgrade to the paid version of their Substack ;)

Donate to their call for mutual aid

Recommend them for a job, if they’re looking and it makes sense

Again, kind of blanking here, but this is a good start. Sound off in the comments!

Before I sign off, let me share:

I feel quite vulnerable for putting all of this information out there! Again, my intention with this post was not for anybody to feel sorry for me, or to feel like I’m complaining about my financial situation. I recognize that I’m deeply, deeply privileged. I have a lot. More than most, even those with full time jobs, I know. My idea of financial security is certainly skewed, having grown up in a pretty affluent city among pretty affluent people. But, I also want to say this: everyone deserves to feel financially secure. All of us, regardless of whether we’re sick or not. I deserve to feel financially secure. You deserve to feel financially secure. My hope in sharing this information is to shed some light on the reality that many of us who are chronically ill are not, and may never be, financially secure.

Thanks for reading. If you have any questions, I’m always here.

xo, Lys

I guess they were… warning me? Warming me about something I didn’t choose to live with? Okay, cool.

This will go up next year — see Footnote 2

I changed my health insurance when I moved (see Footnote 3), and this plan doesn’t fully cover specialty meds like Orencia (a biologic I inject into my thigh every Wednesday evening). Orencia offers copay assistance: a prepaid debit card loaded with $15,000, but these funds ran out in May and won’t reset until January 2025. My current insurance plan covers about 80% of the cost of Orencia—mind you, the actual out-of-pocket cost of Orencia is about $7000 for one month’s supply—and the copay assistance covers the rest. Since it ran out, however, my monthly copay is $500, which, after rent + bills + loans etc, I can’t actually afford with my current income. Next year I’m planning to choose a more comprehensive insurance plan, which will most likely be $550-650 per month.

It was important for Izzy and I to move to a place with less air and noise pollution, with abundant access to nature and fresh air. I recognize that we’re very privileged to even have this choice—many don’t, either because they are dependent on caregivers & doctors who live in cities, because they can’t afford it, because their job is based in a city, etc.

This was a choice. I know that I was never forced to move to a resort town with high rent, but the place we are now fits our needs of being close to nature and also close to an organic grocery store.

I know this number is very high! I feel vulnerable sharing this! Obviously the cost of groceries has risen in recent years. Izzy and I unfortunately don’t tolerate very many foods—we cook most of our meals from scratch, hardly eat out, and opt for the highest quality we can find, which adds up very quickly. My average grocery bill is typically in the high 100s, which other quick trips when we run out of olive oil, for example. We try to all of our produce from the farmer’s market, which adds up to about $60 per week, then supplement with high quality animal protein, gluten free grains, legumes and spices. We also bake our own bread weekly, if not more often, which requires a once-in-awhile big purchase from Azure Standard for various organic, gluten free flours.

I’m talking about things like skincare products that are free from carcinogenic ingredients, microplastics and methylparabens. I’m also talking about air purifiers/their filters, filtered water (which we get in “bulk” from the store) and their glass containers (because plastic containers contain trace amounts of BPA). I’m also talking about clothing & household items made from 100% natural materials instead of polyester, because of the microplastics and general irritation they cause to our sensitive skin barriers. God this is exhausting.

These jobs were service jobs, spending 8 hours standing—making coffee, selling wine, ringing people up at a cash register—which I recognize is very different from an office job where you’re sitting all day. Honestly, I’m interested in giving a full time office job a try at some point (my brain is very fast/has a lot of energy most days) but I’m still worried that the stress and responsibility might be more than I can handle.

Fabulous piece! Thank you so much for your willingness to be explicit about these figures. The financial realities of disability are so poorly understood by those who don't experience them, and the dollars and cents can help bring it home. I think about it all quite a bit— my partner and I are both disabled freelancers and it has massive implications for our future together. Appreciate you shining this spotlight 🔦

Heck yes, all of this, and also oof. Thank you for sharing, and speaking to these realities 💜